By Jesse Colombo (This article was written on May 18th, 2012)

The South Sea Bubble was a speculative bubble in the early 18th century involving the shares of the South Sea Company, a British international trading company that was granted a monopoly in trade with Spain’s colonies in South America and the West Indies as part of a treaty made after the War of the Spanish Succession. In return for these exclusive trading rights, the company assumed England’s war debt. When investors recognized the potential profits to be made from trade with the gold and silver-rich South American colonies, they bid the South Sea Company’s shares  and the shares of similar trading companies to incredible heights in a typical speculative bubble fashion. Not long after virtually all classes of British society were thoroughly engaged in wild stock speculation, the South Sea Bubble popped and stock prices violently collapsed, financially ruining their investors.

and the shares of similar trading companies to incredible heights in a typical speculative bubble fashion. Not long after virtually all classes of British society were thoroughly engaged in wild stock speculation, the South Sea Bubble popped and stock prices violently collapsed, financially ruining their investors.

Events Leading Up to the South Sea Bubble

The South Sea Company was founded in 1711 by the Lord Treasurer Robert Harley and John Blunt, the former director of the Sword Blade Company. During this time, most of the Americas were being colonized and Europeans used the term "South Seas" to refer to South America and other lands located in the surrounding waters. Robert Harley was responsible for creating a mechanism used to fund the British government’s debt that was being incurred during the ongoing War of Spanish Succession of 1701-1713. Due to the fact that the Bank of England’s charter established itself as the only joint stock bank, Harley was unable to establish a bank. Undeterred, Harley established what appeared to be a trading company, but the company’s primary business activity was funding government debt (Melville, 1968).

The British government believed that offering exclusive trading rights with Spain’s colonies would be an effective incentive to convince the private sector to assume the government’s war debts. The South Sea Company’s founders and the government were able to convince shareholders to assume a total of £10 million in short-term government debt in exchange for South Sea Company shares. In return, the government gave shareholders a continual annuity, paying a total of £576,534 each year, or a perpetual loan of £10 million at a 6% yield. This deal resulted in a steady stream of earnings for new shareholders. The government intended to fund interest payments by placing tariffs on goods that were imported from South America (Carruthers, 2005).

When the peace Treaty of Utrecht was signed at the end of the War of Spanish Succession in 1713, the South Sea Company’s trading rights were finally put into writing: the right to supply the Spanish colonies with slaves and to send one trading ship per year. These formalized trading rights were a disappointment to Robert Harley as they were nowhere near as extensive as he had originally expected when he founded the company in 1711 (Harrison, 2001).

By 1717, the South Sea Company had assumed an additional £2 million worth of government debt. By then, government spending for the United Kingdom had reached £64.4 million, which the government was able to afford by lowering the interest rate on its debt. During this time, South Sea Company shareholders continued to collect a reliable stream of earnings. In 1719, a proposal was made by the South Sea Company in which it would purchase over half of the British national debt with new shares alongside a promise to the government that the interest rate on the debt would be reduced to 5% until the year 1727 and 4% for every year after that. This refinancing scheme allowed illiquid high-interest debt to be converted into highly-liquid low-interest debt – a win-win for all parties involved. (Reading, 1933).

As of 1719, the government was in debt by £50 million, £18.3 million of which was held by three of England’s largest corporations. The Bank of England was one of the three corporations and owned £3.4 million of that total debt, while the British East India Company owned £3.2 million and the South Sea Company owned £11.7 million.

The Mania Phase

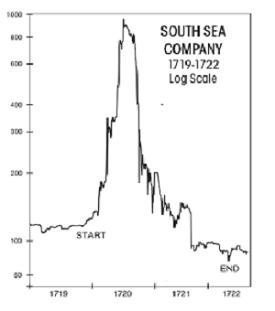

Though the company’s trading rights with Spanish colonies were quite modest, its executives whet investors’ appetites with incredible tales and rumors of South American gold and silver just waiting to imported back to Europe. The company successfully sparked a speculative frenzy for its shares in 1720, with stock prices soaring from £128 in January, £175 in February, £330 in March and £550 in May. The company was able to support unusually high valuations thanks to a £70 million fund of credit that was granted by the King and Parliament for the purpose of commercial expansion (Dickson, 1963).

Shares were offered to a myriad of politicians at market prices. However, these politicians did not purchase the shares in a conventional sense, but held on to their shares with the option sell them back to the South Sea Company at a later date, allowing them to keep all profits made. This purchasing arrangement enticed many government employees as well as the King’s mistress. High ranking shareholders helped to pump the value of South Sea Company shares in addition to lending an air of legitimacy to the scheme (Reading, 1933).

As South Sea Company shares bubbled up to incredible new heights, numerous other joint-stock companies IPOd to take advantage of the booming investor demand for speculative investments. Many of these new companies made outrageous and often fraudulent claims about their business ventures for the purpose of raising capital and boosting their stock prices. Here are some examples of these companies’ business proposals (History House, 1997):

- For supplying the town of Deal with fresh water.

- For trading in hair.

- For assuring of seamen’s wages.

- For importing pitch and tar, and other naval stores, from North Britain and America.

- For insuring of horses.

- For improving the art of making soap.

- For improving of gardens.

- For insuring and increasing children’s fortunes.

- For a wheel for perpetual motion.

- For importing walnut-trees from Virginia.

- For making of rape-oil.

- For paying pensions to widows and others, at a small discount.

- For making iron with pit coal.

- For the transmutation of quicksilver into a malleable fine metal.

And the most outlandish (and cunningly clever!) of all:

- For carrying on an undertaking of great advantage; but nobody to know what it is.

These highly speculative companies were nicknamed "bubbles" and, in an attempt to control them, Parliament passed the “Bubble Act” in 1720 that required new joint-stock companies to be incorporated (Reading, 1933). Ironically, the passing of the “Bubble Act” caused South Sea Company shares to soar to £890 in June 1720. By this time, a full-blown speculative stock frenzy developed in virtually all “bubble” company shares, with all classes of British society taking part in the action. Paupers went from rags-to-riches practically overnight as share prices ballooned to astronomical levels.

The Crash

Though South Sea Company shares were skyrocketing, the company’s profitability was mediocre at best, despite abundant promises of future growth by company directors. Shares leaped to £1000 per share by August 1720 and finally peaked at this level before plunging and triggering an avalanche of selling. The selloff in Company shares was exacerbated by a plan that John Blunt had instituted earlier in the year for the purpose of boosting share prices. The plan entailed the South Sea Company lending investors money to buy its shares, which meant that many shareholders had to sell their shares to cover the plan’s first installment of payments that were due in August (Carswell, 1960).

As South Sea Company and other “bubble” company share prices imploded, speculators who had purchased shares on credit went bankrupt in short order. The popping of the South Sea Bubble resulted in a contagion that popped a concurrent bubble in Amsterdam as well as France’s Mississippi Scheme bubble. When South Sea Company share prices hit a pitiful £150 per share in September 1720, banks and goldsmiths went bankrupt because they were unable to collect loans that they had made to both recently-bankrupted common folk and aristocrats alike. Even Sir Isaac Newton lost a £20,000 (equivalent to about £268 million in present day value) fortune in South Sea Company shares, causing him to remark, "I can calculate the movement of the stars, but not the madness of men" (Wikipedia, n.d.).

Investor outrage led Parliament to open an investigation into the matter in December 1720, resulting in a report that revealed extensive fraud as well as corruption among members of the Cabinet. The Postmaster General was accused along with James Craggs the Elder, James Craggs the Younger, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, John Aislabie , Lord Sunderland and Lord Stanhope. Aislabie was imprisoned and the rest of the Cabinet members were impeached (Melville, 1968). A series of new measures were implemented in order to restore confidence and the estates of the company directors were confiscated in an attempt to remunerate South Sea Company investors. The remaining South Sea Company shares were allocated to the East India Company and the Bank of England. A proposal was even made in Parliament to place bankers in sacks filled with snakes and thrown into the Thames River!

Questions? Comments?

Click on the buttons below to discuss or ask me any question about this topic on Twitter or Facebook and I will personally respond:

Related Web Resources:

History House: The South Sea Bubble

Market Crashes: The South Sea Bubble

The South Sea Bubble (TheSouthSeaBubble.com)

Memoirs of Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds: The South-Sea Bubble

References:

Carruthers, B. (2005). :The First Crash: Lessons from the South Sea Bubble. The American Historical Review, 110(4), 1244-1245.

Carswell, J. (1960). The South Sea bubble. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Dickson, P. M., & Carswell, J. (1963). The South Sea Bubble. The Economic History Review, 16(2), 361.

Harrison, P. (2001). Rational Equity Valuation at the Time of the South Sea Bubble. History of Political Economy, 33(2), 269-281.

Hayley, R. L. (1973). The Scriblerians And The South Sea Bubble A Hit By Cibber. The Review of English Studies, XXIV(93), 452-458.

Melville, L. (1968). The South Sea bubble,. New York: B. Franklin.

Reading, G. R. (1933). The South sea bubble,. New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons.

Temin, P., & Voth, H. (2004). Riding the South Sea Bubble. American Economic Review, 94(5), 1654-1668.

History House.(1997). The South Sea Bubble. Retrieved on 26th May, 2012, from, http://www.historyhouse.com/in_history/south_sea/

Wikipedia.(n.d.). South Sea Company. Retrieved on 26th May, 2012, from, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/South_Sea_Company