By Jesse Colombo (This article was written on June 4th, 2012)

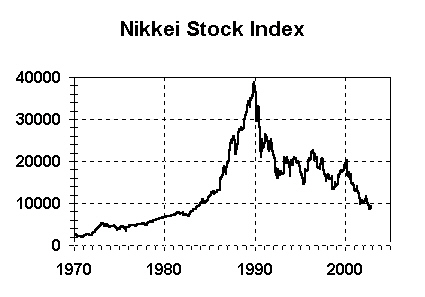

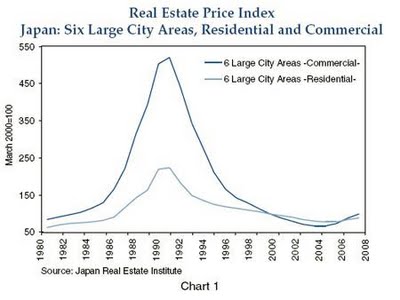

In the late 1980s, on the heels of a three-decade long “Economic Miracle,” Japan experienced its infamous “bubble economy” in which stock and  real estate prices soared to stratospheric heights driven by a speculative mania. Japan’s Nikkei stock average hit an all-time high in 1989, only to crash in a spectacular fashion shortly after, causing their real estate bubble to collapse and throwing the country into a severe financial crisis and long period of economic stagnation known as the “Lost Decades.”

real estate prices soared to stratospheric heights driven by a speculative mania. Japan’s Nikkei stock average hit an all-time high in 1989, only to crash in a spectacular fashion shortly after, causing their real estate bubble to collapse and throwing the country into a severe financial crisis and long period of economic stagnation known as the “Lost Decades.”

Events Leading Up to Japan’s Economic Bubble

Japan’s highly traditional society experienced significant changes after their defeat in the Second World War due, in part, to the Westernizing influences of the occupying Allied Forces (Molasky, 1999). The U.S.’ Marshall Plan provided aid to rebuild Japan’s economy and the two countries’ improving relationship created an opportunity for Japan to export manufactured products to the increasingly-affluent United States.

Japanese industry was first dominated by large family-controlled industrial and financial business conglomerates known as zaibatsu (translated as “financial clique”), which evolved into keiretsu business conglomerates in the latter half of the twentieth-century. Typical keiretsu conglomerates were arranged in the form of a series of interlocking industrial corporations organized around a Japanese bank, which provided banking and financial services to the  industrial corporations. Most corporations within a keiretsu conglomerate carried names that were variants of their keiretsu’s overarching brand name, for example: Mitsubishi Bank, Mitsubishi Corporation, Mitsubishi Heavy Industries and Mitsubishi Motors. Other examples of keiretsu conglomerates are Sumitomo, Mitsui, Fuyo, Dai-Ichi Kangyo and Sanwa (Wikipedia, n.d.). Starting in the 1950s and accelerating during Japan’s bubble, keiretsu corporations purchased each other’s shares to form an extensive network of cross-holdings, a practice that was seen as important for guaranteeing long-term stability and developing lasting business relationships. (Web-Japan.org, n.d.).

industrial corporations. Most corporations within a keiretsu conglomerate carried names that were variants of their keiretsu’s overarching brand name, for example: Mitsubishi Bank, Mitsubishi Corporation, Mitsubishi Heavy Industries and Mitsubishi Motors. Other examples of keiretsu conglomerates are Sumitomo, Mitsui, Fuyo, Dai-Ichi Kangyo and Sanwa (Wikipedia, n.d.). Starting in the 1950s and accelerating during Japan’s bubble, keiretsu corporations purchased each other’s shares to form an extensive network of cross-holdings, a practice that was seen as important for guaranteeing long-term stability and developing lasting business relationships. (Web-Japan.org, n.d.).

Keiretsu conglomerates received a very high-level of support from the Japanese government – a system of crony capitalism that became known as “Japan, Inc.,” which was both revered and reviled by Western commentators and executives for its unfair advantage over domestic businesses.

Japanese industry gained its competitive edge by copying Western products, improving upon them and selling them back to the West for cheaper prices. To compensate for their relative lack of natural resources, Japanese companies focused their efforts on developing innovative and efficient manufacturing methods and improving the quality of their products, giving Japan a strong competitive  advantage in high value export products such as cars and electronics (BPIR, 2002). By the late 1970s, Japan’s use of assembly-line robots in automobile manufacturing, which made human error nonexistent and boosted overall quality, sent shivers throughout the U.S. automobile industry, which was still assembling cars by hand. In addition, the rolling energy crises of the 1970s reduced the appeal of traditional gas-guzzling American-style V8 automobiles and dramatically increased consumer interest in the smaller, more fuel-efficient vehicles made by Japanese auto makers such as Honda and Datsun (now Nissan).

advantage in high value export products such as cars and electronics (BPIR, 2002). By the late 1970s, Japan’s use of assembly-line robots in automobile manufacturing, which made human error nonexistent and boosted overall quality, sent shivers throughout the U.S. automobile industry, which was still assembling cars by hand. In addition, the rolling energy crises of the 1970s reduced the appeal of traditional gas-guzzling American-style V8 automobiles and dramatically increased consumer interest in the smaller, more fuel-efficient vehicles made by Japanese auto makers such as Honda and Datsun (now Nissan).

By the 1970s and 1980s, Japan extended its domination to the global electronics industry as it manufactured the majority of the world’s consumer electronics products and introduced innovative and revolutionary new products such as the pocket transistor radio, the VHS recorder and the Sony Walkman, which created a consumer love affair that was similar to the Apple iPod and iPhone craze of recent years. Japanese electronics manufacturers also established a strategic foothold in the burgeoning computer hardware industry, virtually  monopolizing the market for semiconductor chips, circuit boards and other computer components – nearly everything except for CPU chip production, which was still dominated by American companies. In the 1980s, many people believed that the Japanese firms Sony and Hitachi would eventually acquire American electronics bellwethers Intel and IBM. Japan’s role as “King of the Global Electronics Industry” was solidified after the American video game industry experienced a severe bust in the early 1980s, creating the opportunity for Japanese video game powerhouses Nintendo and Sega to practically corner the exploding video game market.

monopolizing the market for semiconductor chips, circuit boards and other computer components – nearly everything except for CPU chip production, which was still dominated by American companies. In the 1980s, many people believed that the Japanese firms Sony and Hitachi would eventually acquire American electronics bellwethers Intel and IBM. Japan’s role as “King of the Global Electronics Industry” was solidified after the American video game industry experienced a severe bust in the early 1980s, creating the opportunity for Japanese video game powerhouses Nintendo and Sega to practically corner the exploding video game market.

Japan’s “Economic Miracle” of the late-twentieth century caused the country’s standard of living to soar to among the highest in the world and its people had the world’s longest life expectancy. By the 1980s, Japan’s GDP per capita rivaled or even surpassed many Western countries and the country became the world’s largest creditor nation. Japanese men clamored to work as “salarymen” or white-collar professionals for the country’s keiretsu corporations. Though salarymen worked extremely long hours and were expected to provide the utmost loyalty and sacrifice to their corporation, they were rewarded with thoroughly middle class lifestyles and promises of lifetime employment – a significant step-up from the very humble lives that most Japanese lived before World War Two.

The Bubble Phase

Japan’s booming post-War export economy and strict fiscal policies that were meant to encourage household savings resulted in a cash surplus in the country’s banking system that eventually led to more lenient lending. The country’s healthy trade surpluses and the Plaza Accord in 1985, which sought to weaken the U.S. dollar against the Yen and German Deutsche Mark, caused the Yen currency to appreciate against other currencies, which in turn made foreign capital investments relatively inexpensive for Japanese companies.

The combination of excess liquidity in the banking system, financial deregulation and the country’s export “miracle” eventually led to overconfidence and overexuberance in Japan’s economy, which became the second largest economy in the world after the USA in just a few decades. Banks started to take increasingly excessive risks that were partly funded by 186 trillion worth of Yen borrowed from various capital markets.

Nearly $40 billion was invested in risky leveraged buyouts in the USA, including 40% of the amount used in the buyout of RJR Nabisco, which ended in the biggest corporate scandal in the USA at the time and became the topic of the book (and the film), ‘Barbarians at the Gate’ (Watkins, 1994). In 1990, a Japanese business group acquired the Pebble Beach golf course, causing the U.S. Open—a highly prestigious golf tournament—to be played on a foreign-owned golf course for the first time ever (New York Times, 1990). Other famous American institutions acquired by Japanese business interests were the Rockefeller Center and Columbia Pictures of Hollywood (Powel, 2009).

Overconfidence and the Bank of Japan’s loose monetary policy in the mid-to-late 1980s led to aggressive speculation in domestic stocks and real estate, pushing the prices of these assets to previously unimaginable levels. From 1985 to 1989, Japan’s Nikkei stock index tripled to 39,000 and accounted for more than one third of the world’s stock market capitalization (Economist, 2011). The keiretsu conglomerates’ practice of cross-holding each other’s shares played a significant role in boosting stock prices and caused Japanese corporate wealth to balloon along with stock prices. In addition, many Japanese corporations practiced a corporate invention known as “zaitech” or “financial engineering,” in which speculative profits and capital gains were reported as income on corporate financial statements. Zaitech-practicing firms obtained low-interest loans and used them to purchase stocks and real estate, which surged and helped the firms to report blowout earnings as long as asset prices continued to rise. At one point, it was estimated that an incredible 40-50% of Japanese corporate earnings were derived from zaitech. (GreekShares.com, n.d.) At the very peak of the bubble, a 1989 survey of institutional investors showed that the majority of them did not believe that the Nikkei was overvalued (Barsky, 2009, p. 32).

Real estate prices experienced similar manic action, with prices in Tokyo’s prime neighborhoods rising to levels that made them 350 times more expensive than comparable land in Manhattan, New York (Investopedia, 2010). The land underneath the Tokyo Imperial Palace was rumored to have been worth as much as the entire state of California in the same year (Impoco, 2008).

Soaring stock and real estate prices generated astounding amounts of “bubble wealth” in Japan, some of which found its way into the art market and created an art bubble. Record prices were paid for famous pieces of Western art. In 1987, a Japanese insurance company paid almost $40 million for Vincent van Gogh’s ‘Sunflowers’—a version which was later claimed to actually be a fake. This was topped by Ryoei Saito, a paper industry billionaire, who paid $82.5 million for another painting of van Gogh, ‘Dr. Gachet.’ He admitted that he paid $30 million more than he had planned, but that he did not care since he wanted it so much anyway (Associated Press, 1998). Wealthy Japanese tourists became an ever-present fixture in the high-end auction houses, art galleries and luxury boutiques of cities like New York and London.

The Crash

By 1989, Japanese officials became increasingly concerned with the country’s growing asset bubbles and the Bank of Japan decided to tighten its monetary policy. Soon after, the Nikkei stock bubble popped and plunged by nearly 50% from approximately 39,000 to 20,000 during the year 1990, hitting 15,000 by 1992. Japan’s imploding stock bubble also popped the country’s real estate bubble, creating zaitech-in-reverse and throwing the country into a deep financial crisis and halting the three-decade old “Economic Miracle” in its tracks.

Japan’s deteriorating competitive edge against other Asian exporters, including China and South Korea, and its steadily deflating stock and property prices during the 1990s and 2000s have resulted those decades being called “Lost Decades.” During this time, many unprofitable and debt-ridden companies were kept afloat through frequent government bailouts, leading to their nickname, “Zombie companies.” By 2004, residential real estate in Tokyo was only worth of 10% of its late 1980s peak, while the most expensive land in Tokyo’s Ginza business district had fallen back to just 1% of its 1989 level in the same year (Barsky, 2009). Similarly, the Nikkei stock index is now trading around 10,000, just little over a quarter of its all-time high. It has been over two decades since the popping of Japan’s economic bubble and the country is still actively battling with deflationary forces that are so powerful that near-zero interest rates (zero-interest rate policy or ZIRP), repeated bouts of quantitative easing (some call it “money printing”) and constant Yen-weakening currency interventions have barely made a dent.

Questions? Comments?

Click on the buttons below to discuss or ask me any question about this topic on Twitter or Facebook and I will personally respond:

Related Web Resources:

Wikipedia: Japanese asset price bubble

Wikipedia: Japanese post-war economic miracle

Life After the Bubble: How Japan Lost a Decade

Wikipedia: Lost Decade (Japan)

References:

Associated Press (1998), Japanese collectors begin to unload bubble-era art, published in The Augusta Chronicle. Retrieved March 16, 2012, from:http://chronicle.augusta.com/stories/1998/07/16/ent_233468.shtml

Barksy, R. B. (2009), The Japanese Bubble: A ‘Heterogeneous’ Approach. NBER Working Paper Series. Retrieved March 14, 2012, from National Bureau of Economic Research Website: http://www.nber.org/papers/w15052.pdf

Bloomberg (2010), China Overtakes Japan as World’s Second-Biggest Economy. Bloomberg News, August 16, 2010. Retrieved March 20, 2012, from: http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2010-08-16/china-economy-passes-japan-s-in-second-quarter-capping-three-decade-rise.html

BPIR (2002), History of Quality. Retrieved March 20, 2012 from the Business Performance Improvement Resource website: http://www.bpir.com/total-quality-management-history-of-tqm-and-business-excellence-bpir.com.html

Impoco, J. (2008), Life After The Bubble: How Japan Lost a Decade, published in New York Times, retrieved March 16, 2012 from:http://www.nytimes.com/2008/10/19/weekinreview/19impoco.html?_r=2

Investopedia (2010), 5 Steps of a Bubble. Retrieved March 14, 2012, from Investopedia Website: http://www.investopedia.com/articles/stocks/10/5-steps-of-a-bubble.asp#axzz1p5r28bBE

Molasky, M. S. (1999), The American Occupation of Japan and Okinawa. Published by Routledge.

New York Times (1990), Japanese Buy Pebble Beach Golf Course. Retrieved March 16, 2012: http://www.nytimes.com/1990/09/07/business/japanese-buy-pebble-beach-golf-course.html

New York Times (2011), China’s Scary Housing Bubble. Published on April 14, 2011. Retrieved March 20, 2012 from:http://www.nytimes.com/roomfordebate/2011/04/14/chinas-scary-housing-bubble?ref=global

Watkins, T. (1994), The Bubble Economy of Japan. San José State University, Department of Economics. Retrieved March 20, 2012, from:http://www.sjsu.edu/faculty/watkins/bubble.htm

GreekShares.com (n.d.). The Japanese Zaitech Bubble. Retrieved May 30th, 2012 from

http://www.greekshares.com/japanese.php

Wikipedia (n.d.). Keiretsu. Retrieved May 30th, 2012 from

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Keiretsu

Web-Japan.org (n.d.). Breaking Off Ties: Firms Selling Off Cross Held Shares. Retrieved May 30th, 2012 from

http://web-japan.org/trends00/honbun/tj010111.html