By Jesse Colombo (This article was written on June 23rd, 2012)

The Mississippi Bubble was an economic bubble in France in the early 1700s that developed in parallel with Britain’s disastrous South Sea Bubble. The mastermind behind the Mississippi Bubble was John Law, a Scottish financier, gambler and playboy who ascended into the upper echelons of French public finance through his friendship with the Duke of Orléans. Law became the French government’s primary financial advisor and used this power to establish the Banque Générale, a bank with the authority to issue “paper” money, as well as the Mississippi Company (later called "the Compagnie des Indes"), which was granted a monopoly on the development of France’s vast Mississippi Territory in North America. When investors started salivating over the supposedly immense bounty of resources in the Mississippi Territory, including gold and silver, they bid Compagnie des Indes shares up to astronomical heights. Unfortunately, the company’s prospects turned out to be little more than empty promises and the shares crashed back down to earth, taking down France’s stock market and public finances with it.

The Mississippi Bubble was an economic bubble in France in the early 1700s that developed in parallel with Britain’s disastrous South Sea Bubble. The mastermind behind the Mississippi Bubble was John Law, a Scottish financier, gambler and playboy who ascended into the upper echelons of French public finance through his friendship with the Duke of Orléans. Law became the French government’s primary financial advisor and used this power to establish the Banque Générale, a bank with the authority to issue “paper” money, as well as the Mississippi Company (later called "the Compagnie des Indes"), which was granted a monopoly on the development of France’s vast Mississippi Territory in North America. When investors started salivating over the supposedly immense bounty of resources in the Mississippi Territory, including gold and silver, they bid Compagnie des Indes shares up to astronomical heights. Unfortunately, the company’s prospects turned out to be little more than empty promises and the shares crashed back down to earth, taking down France’s stock market and public finances with it.

Events Leading Up to the Mississippi Bubble

The Mississippi Bubble saga began in 1715, when the French government was teetering on the verge of insolvency under the burden of debts incurred during the War of Spanish Succession. In time, the government defaulted on a portion of its debt, lowered its interest payments and raised taxes to very high levels, all of which served to depress the French economy and caused the value of its gold and silver-backed currency to fluctuate wildly. The French government, then led by a group of regents because King Louis XV was only five-years old, desperately scrambled to find a solution to the nation’s fiscal and economic woes. The Duke of Orléans, the leader of the group of regents, soon decided to seek the council of his friend, John Law, who was an early theorist of monetary economics.

John Law hailed from Fife, Scotland, where he was born into an affluent family of bankers and goldsmiths. Law became his father’s apprentice at age fourteen and studied the banking business until his father’s death three years later. Soon after, Law travelled to London in pursuit of adventure and earned a living as a gambler thanks to his keen mathematical abilities. In London, the twenty-three year old Law became involved in a duel over a lady friend in which he swiftly killed his opponent and was charged with murder and sentenced to death. John Law spent a brief time in prison before he escaped to mainland Europe, where he studied high finance in cities such as Amsterdam, Venice and Genoa. In 1705, Law published an academic paper in which he argued against the use of precious-metal backed currency in favor of “paper” or fiat currency, claiming that the use of fiat currency would stimulate commerce (Smant, 2001). Due to these distinct views, Law is often considered to be an early Keynesian-style economist.

John Law hailed from Fife, Scotland, where he was born into an affluent family of bankers and goldsmiths. Law became his father’s apprentice at age fourteen and studied the banking business until his father’s death three years later. Soon after, Law travelled to London in pursuit of adventure and earned a living as a gambler thanks to his keen mathematical abilities. In London, the twenty-three year old Law became involved in a duel over a lady friend in which he swiftly killed his opponent and was charged with murder and sentenced to death. John Law spent a brief time in prison before he escaped to mainland Europe, where he studied high finance in cities such as Amsterdam, Venice and Genoa. In 1705, Law published an academic paper in which he argued against the use of precious-metal backed currency in favor of “paper” or fiat currency, claiming that the use of fiat currency would stimulate commerce (Smant, 2001). Due to these distinct views, Law is often considered to be an early Keynesian-style economist.

When the desperate Duke of Orléans came looking to John Law for help, Law viewed it as an opportunity to put his monetary theory into action. In 1716, Law received the French government’s permission to establish a national bank, the Banque Générale, which took in deposits of gold and silver and issued “paper” bank notes in return. The bank notes issued by Banque Générale were not legal tender but were accepted as such by the French public because they were redeemable in official French currency. Banque Générale built up its bank reserves through the issuance of stock and from profits earned through the management of the French government’s finances.

Source: Nova Scotia’s Electric Scrapbook

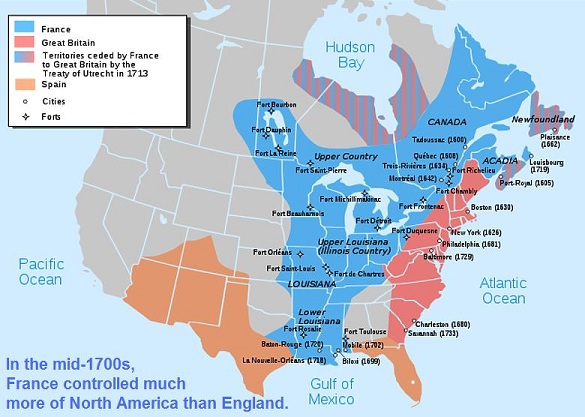

In 1717, John Law used his growing rapport within French society to acquire a struggling trading company, the Mississippi Company, which he renamed to “the Compagnie d’Occident” (the Company of the West) and was granted a monopoly on trade with and development of France’s North American colonies along the Mississippi River. These territories (see chart above) spanned a wide swath of area from present-day Louisiana up to Canada and were considered to be valuable for their abundance of resources such as beaver skins and precious metals (which later proved to be untrue). As Law’s influence continued to grow, the Compagnie d’Occident’s name was changed to “Compagnie des Indes (“Company of the Indies”) and according to David Smant, “expanded to monopolize all French trade outside Europe. In July 1719 the Compagnie purchased the right to mint new coinage. In August 1719 the Compagnie bought the right to collect all French indirect taxes and in October 1719 the Compagnie took over the collection of direct taxes. Finally, a plan was launched to restructure most of the national debt, whereby the remainder of existing government debt would be exchanged for Compagnie shares.” By this time, John Law had amassed an incredible amount of power as his companies now controlled both France’s foreign trade and its finances.

The Bubble Phase

Chart Source: HenryThornton.com

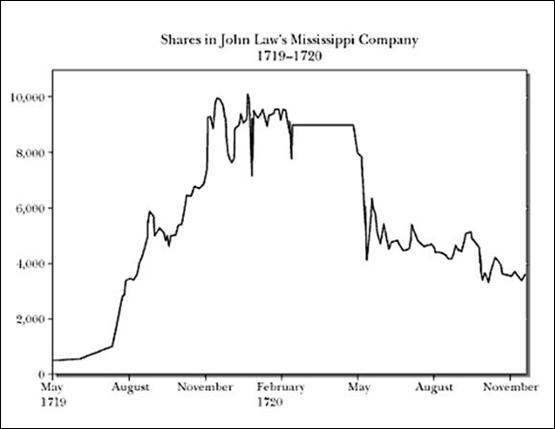

In January 1719, the Compagnie des Indes offered shares to the public for 500 livres per share (livres were France’s currency at that time), which were bought and paid for with Banque Générale bank notes or with government debt. Compagnie shares soared to an incredible 10,000 livres per share by December 1719 as investors began to lust over the company’s potential value of trade with the supposedly gold and silver-rich French colonies. With share prices at such high levels, John Law had gone from a broke gambler to one of the wealthiest, most powerful men in Europe. People of all social classes invested in Compagnie des Indes shares, causing many paupers to become very rich in a short span of time. Incidentally, the French word “millionaire” originated as a result of the many people that were made wealthy as Compagnie shares soared (Moen, 2001).

Explosive demand for Compagnie des Indes shares caused the total amount of “paper” money bank notes in circulation to increase 186% in one year due to the fact that Banque Générale issued as much bank notes as the public demanded. This expansion of the money supply resulted in a powerful inflationary episode in which the price of goods doubled between July 1719 and December 1720. A good portion of Compagnie des Indes share price gains were due to this inflation as well (Smant, 2001). Paris experienced a “bubble economy”-type boom as real estate prices and rents soared twenty-fold and wealthy speculators clamored to buy luxury goods (Sebastian, 2011). According to Charles Mackay, “New houses were built in every direction, and an illusory prosperity shone over the land, and so dazzled the eyes of the whole nation, that none could see the dark cloud on the horizon announcing the storm that was too rapidly approaching.”

Soon, Banque Générale had issued vast quantities of bank notes even though they did not have an equivalent amount of gold and silver-based legal tender for everyone who eventually wished to redeem their notes. It is likely that John Law had expected to fulfill Banque Générale’s precious metals deficit with gold and silver imported from North America by the Compagnie des Indes.

The Crash

In January 1720, Compagnie des Indes shares began to fall as some investors decided to take their profits in the form of gold coins. John Law tried to curb the sell-off by limiting payments in gold of more than 100 livres (Moen, 2001). A scandal ensued in May 1720, when John Law decided that Compagnie shares were overvalued, causing him to start devaluing shares. In addition, Banque Générale notes were devalued by 50%, presumably due to the bank’s precious metals deficit, which was unable to be fulfilled by Compagnie des Indes’ operations in North America because the Mississippi Valley region lacks meaningful deposits of precious metals (the discovery of which resulted in major investor disappointment). Law’s devaluation of shares and bank notes caused an intense public uproar, which resulted in a compromise in which the bank notes’ value was restored but payment in precious metals was stopped. Despite the compromise, the French public was outraged against the Compagnie and its near-worthless paper bank notes.

The combination of aggressive investor selling and Law’s devaluations caused Compagnie des Indes shares to collapse from 10,000 livres to 1,000 livres by December 1720 (Moen, 2001). Compagnie investors were financially-ruined and many former millionaires became paupers. By the end of 1720, John Law was viewed as a scam artist and his rivals were given control over two-thirds of his companies’ shares. Share prices further deflated to 500 livres in 1721 (Moen, 2001). Soon after, John Law escaped France, disguised as a woman for his own safety, and spent the rest of his life as an impoverished gambler in various parts of Europe. The collapse of Banque Générale and the Compagnie des Indes, which coincided with the popping of Britain’s South Sea Bubble, plunged France and other European countries into a severe economic depression and laid the groundwork for the French Revolution that occurred later on in the century.

Although traditionally considered a bubble, the Mississippi Bubble wasn’t actually a bubble, in a precise technical sense. A bubble is primarily caused by widespread mania and speculation, followed by a brutal collapse in asset values. In contrast, the Mississippi Bubble was the result of failed monetary policies that caused excessive money supply growth and inflation.

Questions? Comments?

Click on the buttons below to discuss or ask me any question about this topic on Twitter or Facebook and I will personally respond:

Related Web Resources:

Famous First Bubbles: Mississippi Bubble

John Law and the Mississippi Bubble 1718-1720

Encyclopedia Britannica: Mississippi Bubble

Wikipedia: Mississippi Company

Wikipedia: John Law (economist)

References:

Costain, T. B. (1955). The Mississippi Bubble: New York: Random House.

Garber, Peter.“Famous First Bubbles,” in Speculative Bubbles, Speculative Attacks, and Policy Switching, Robert Flood and Peter Garber, eds . (MIT Press: Cambridge MA, 1994)

Hough, E. (1902). The Mississippi bubble; how the star of good fortune rose and set and rose again, by a woman’s grace, for one John Law of Lauriston; a novel,. Indianapolis: Bowen-Merrill.

Hough, E. (1902). The Mississippi bubble. New York: McKinlay, Stone & Mackenzie.

Kindleberger, Charles. Manias, Panics, and Crashes, 3rd ed. (Wiley: New York 1996).

Mackay, Charles. The Mississippi Scheme (Andrew Pub. Co.: 1980).

Mississippi Bubble. (2012). In Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved on 24th April 2012, from http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/385600/Mississippi-Bubble

Moen, Jon. (2001). John Law and the Mississippi Bubble: 1718-1720. Retrieved on 25th April 2012, from http://mshistory.k12.ms.us/articles/70/john-law-and-the-mississippi-bubble-1718-1720

Sebastian, J.F. (2011). The Mississippi Bubble and the French Bailout. The Prepare and Prosper Website. Retrieved on 7th June 2012, from

http://www.prepareandprosper.net/the-mississippi-bubble-and-the-french-bailout/

Smant, David. (2001) Famous First Bubbles? Mississippi Bubble. Homepage of D.J.C. Smant. Erasmus School of Economics. Retrieved on 7th June 2012, from

http://people.few.eur.nl/smant/m-economics/bubbles/johnlaw.htm.

Thiers, A., & Fiske, F. S. (1859). The Mississippi Bubble: A Memoir of John Law. New York: W.A. Townsend & Company.